Preterm Birth in Harar town public health hospitals

Gosaye Teklehaymanot Zewde

RMV, Bsc Nurse, Msc in Maternity and Neonatal Nsg, Department of Midwifery, Harar Health Science College, Harar, Ethiopia.

ABSTRACT

Background: Preterm birth is defined as a delivery that occurs at less than 37 weeks of gestation. The majority of preterm birth remains vulnerable to long term complications that may persist all over their lives. Globally, about 12.9 million births (9.6%) of all births worldwide were preterm and of these more than 60% of preterm births occur in Africa and South Asia while about 0.5 million were in each of Europe and North America. There is limited evidence on the magnitude of preterm birth and associated factors among women attending delivery service at public hospitals of low-income countries like Ethiopia including the study setting, Harar town. Objective: To assess the magnitude of preterm birth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in public health hospitals in Harar town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2019. Methods and material: An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted on 325 women attending delivery service in Harar public hospitals. Structured questionnaires were used to collect data; a systematic sampling technique was also used to select participants. A total of three data collectors and one supervisor participated in the study. The data was entered into SPSS version 22.0 for analysis. Pretest, double data entry and local language translation were used to assure data quality. Descriptive and logistic analysis was employed. To measure the strength of association between dependent and independent variables, Crude and Adjusted Odd Ratios with 95% confidence interval were calculated. Finally, the variable which shows p-value<0.05 considered as statistically significant. Result: The study showed that the magnitude of preterm birth was 24.9% (95%CI 21.0, 29.8). Women who didn’t attend ANC (AOR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.7, 2.3), with a history of antepartum hemorrhage (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 0.2, 2.7), hemoglobin less than eleven (AOR=1.4, 95% CI: 0.2, 2.2), birth interval less than 24 months (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 0.4, 2.3), and history of chronic disease (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 0.4, 2.3) were significantly associated with the outcome variable. Conclusion and recommendation: The prevalence of preterm birth in Harar town public health hospitals is slightly higher than studies done in different parts of Ethiopia. Not attending ANC, short interpregnancy interval (<24 months), previous history of APH, presence of chronic medical illness, and low hemoglobin level (<11g/dl) were found to be statistically significant with the occurrence of preterm birth in the current pregnancy, therefore, efforts are needed to improve it.

Key Words: Laboring mother, Preterm birth, public hospital, Harar Town.

INTRODUCTION

Developing countries are more seriously faced with pregnancy-related complications [1]. Preterm birth is defined by WHO as all viable births before 37 completed weeks of gestation or fewer than 259 days since the first day of a woman’s last menstrual period [2]. It is classified as extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28 to <32 weeks), and moderate preterm (32 to < 37 weeks), which can also be spontaneous or provider-initiated (induced) [3]. Globally, about 12.9 million births (9.6%) of all births worldwide were preterm; of these, more than 60% of preterm births occurred in Africa and South Asia, about 0.5 million in each of Europe and North America, and 0.9 million in Latin America and the Caribbean [4]. The rate of preterm birth is escalating globally and ranges from 5 to 7% in developed countries and significantly higher in the least developed countries [5]. Respiratory problems are the main cause of death and hospitalization for preterm neonates [6]. Prematurity is one of the leading causes of neonatal deaths in Africa (11.9%) and is a major public health problem and responsible for 27% of all early neonatal admission [7, 8]. According to the report from “white paper on preterm birth” in 2011, of all 4 million annual early neonatal deaths, 28% are due to preterm birth [9]. Preterm birth has many long and short-term consequences like cerebral palsy, mental retardation, visual and hearing impairments, behavior and social-emotional concerns, learning difficulties, poor health and growth, neurosensory deficits (blindness, deafness), intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enter colitis, and delay in physical and mental development [10, 11]. The major risk factor of preterm delivery is the absence or inadequate prenatal care, low monthly income, no contraceptive use, cesarean delivery, and clinical complications during pregnancy [12]. There is limited information on the magnitude of preterm birth and associated factors among women attending delivery service at public hospitals of Harar Town. Therefore, this study aimed to contribute in identifying magnitude and factors associated with preterm birth.

The result of this study provides valuable information on the magnitude of preterm birth and associated factors. Determining factors has a great role in guiding health professionals and health policymakers to design the intervention strategy and applying necessary preventive and appropriate measures to decrease preterm birth and newborn mortality and morbidity. Besides, it will help to fill the research gaps in the study area and serve as baseline information for other researchers.

The general objective of the study was to assess the magnitude of preterm birth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in public health hospitals in Harar town, eastern Ethiopia, 2019. The Specific objectives included assessing the magnitude of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth in public health hospitals and identifying factors associated with preterm birth among mother who gave birth in public health hospitals from April 11 to May 17, 2019

METHODOLOGY

Study area and study period

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted among mothers who gave birth in Harar Town public health institutions. Harar is located in the eastern part of Ethiopia, 525 Km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. In the region, 27 health posts, 8 health centers, 2 public, 2 private, 1 federal police, 1 Fistula Hospitals, 18 Private for-profit clinics, 25 pharmaceutical retails outlets, 3 pharmaceutical whole sellers and 2 modern laboratories are available. The study was conducted in 2 public hospitals namely Jugel and Hiwot Fan Specialized university hospital from April 11 to May 17, 2019.

Study design: A quantitative institutional-based cross-sectional study was utilized.

Source and study population: The source of the population was mothers who gave birth in Harar town public hospitals and the study population were randomly selected from mother who gave birth during the study period

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women who gave birth during the study period with known LNMP or had an ultrasound check-up during pregnancy were included in this study. Women who didn’t have consent, or were unable to communicate were excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined by using single population proportion formula; the proportion of preterm birth from the study conducted in Jimma was 25.9% [13]; the calculated sample size was 295 and by adding 10% non-response rate the final Sample was 325. By using double population proportion formula (P1=23.46 %, P2= 9.64%, 95% margin of error of 5 % and power of 80%, and using Open Epi Info 7) [14], the calculated sample size was 254, and by adding 10 % non-response rate the final Sample was 279. By comparing the first and second objectives, the final sample size was 325.

Sampling Procedure

Two governmental public hospitals were included. The sample was proportionally allocated based on their patient flow. The average monthly patient flows in two hospitals were 402 and 180 at HFSUH and Jegula Hospital. The sampling frame was developed from the delivery registration book and subjects were selected by using a systematic random sampling method. Finally, a total of 325 participants were selected based on their allocation until the desired sample size was met.

Schematic description of the sampling procedure.

Figure 1. Schematic description of the sampling procedure of research conduct on the magnitude of preterm birth and associated factors among pregnant women attending delivery service in public hospitals of Harar town, 2019.

Variables of the study

Dependent variables: Preterm Birth.

Independent variables: Socio-demographic factors, maternal age, maternal educational status, residence, and maternal occupational status.

Health care service utilization-related factors: ANC follow up status and number of ANC visits. Obstetric related factors: Parity, interpregnancy interval, the onset of labor, and history of preterm birth, pregnancy outcome, PIH, APH, and PROM.

Medical-related factors: Maternal HIV status, malaria during pregnancy, anemia (hemoglobin level) during pregnancy, and chronic illnesses (like cardiac, DM, asthma, and hypertension).

Data collection tools and procedure: The interviewer-administered questionnaire was adopted after reviewing relevant scientific literature. The tool was translated into local language Afan Oromo and translated back to the English language to check its consistency. The questionnaire contains socio-demographic, obstetrics, health care service utilization and medical-related factors. Data were collected by three diplomae and one BSc Midwives.

Data quality control: To assure the quality of the data, a properly designed data collection instrument was developed and a pretest was conducted. The training was given for data collectors and supervisors for three days on the instruments, method of data collection, ethical issues, and purpose of the study. Completeness and correctness of data were checked daily.

Data processing and analysis: Data entry was done by using Epi-info 3.1 and transferred to SPSS version 21 for analysis. The univariate analysis such as proportions, percentages frequency distributions and appropriate graphic presentations as well as measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion were made. Inferential statistics were used to establish associations between prematurity and the various risk factors using a chi-square analysis. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the factors independently associated with preterm birth. In binary logistic regression, analyses with p ≤ 0.25 were transferred to multivariate logistic regression analysis. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, the variables with P-value ≤ 0.05 were considered as variables significantly associated with preterm birth.

Ethical clearance: Ethical clearance letter was obtained from Harar health Science College Ethical Review Committee. Permission was obtained from the study institution. All the participants were informed about the purpose, advantages, and disadvantages. They had the right to be involved or not. Consent was obtained from each respondent before data collection. Confidentiality was maintained by avoiding names and other personal identification.

Operational definitions

Preterm birth: Refers to the birth of a baby before completion of 37 weeks of gestation (2).

Term birth: Refers to the birth of a baby after completion of 37 weeks of gestation (2).

Last menstrual period: The date of the starting of last menstruation (12).

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 325 mothers were included in the study which made the response rate of 100 %. The mean age of the study participants was 27.02 with ±5.73 SD. The majority of the study participants (200; 61.5%) were between 20 and 30 years old. Regarding ethnicity majority, 161 respondents (49.5%) were Oromo, and 158 (48.6%) were Muslim (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of women who give birth in public hospitals in Harar town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2019.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Age |

< 20years 21-30 years 31-40 years |

19 200 106 |

5.8 61.5 32.7 |

|

Residency |

Urban Rural |

146 179 |

44.9 55.1 |

|

Religion |

Muslim Orthodox Protestant |

158 107 60 |

48.6 32.6 18.5 |

|

Ethnicity |

Oromo Amhara Harari Tigray Somali |

161 106 35 15 8 |

49.5 32.6 10.8 4.6 2.5 |

|

Education of mother |

Can’t read and write Can read and write Primary level Secondary and above |

101 110 90 25 |

31.7 33.8 27.7 0.8 |

|

Occupation of mother |

Government Private Merchant |

128 115 82 |

39.4 35.4 25.2 |

Obstetric-related Characteristics

The majority of the respondents (227; 69.8%) were multigravida women. Regarding birth interval, 164 women (72.2%) had less than two years of birth interval. Spontaneous vaginal delivery accounts for the most prevalent mode of delivery (240; 73.8%). Nearly one third (99; 30.5%) of women had a history of abortion. while more than half (180; 55.4%) of the pregnancies were planned. The majority of women’s labor (282; 86.8%) started spontaneously, 250 women (76.9%) had no history of liquid drainage before labor.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Ever give birth |

Yes |

227 |

69.8 |

|

No |

98 |

30.2 |

|

|

Inter birth interval |

≤ 2 years |

164 |

72.2 |

|

3-5 years |

56 |

24.7 |

|

|

> 5 years |

7 |

3.1 |

|

|

Current mode of delivery |

SVD |

240 |

73.8 |

|

C/S |

70 |

21.5 |

|

|

Instrumental |

15 |

4.7 |

|

|

Pregnancy outcome |

Single tone |

243 |

74.8 |

|

Multiple |

82 |

25.2 |

|

|

History of preterm |

Yes |

85 |

26.8 |

|

No |

240 |

73.8 |

|

|

History of abortion |

Yes |

99 |

30.5 |

|

No |

226 |

69.5 |

|

|

Pregnancy type |

Planned |

180 |

55.4 |

|

Unplanned |

145 |

44.6 |

|

|

Labor onset |

Spontaneous |

282 |

86.8 |

|

Induced |

43 |

13.2 |

|

|

Liquid drainage before labor |

Yes |

75 |

23.1 |

|

No |

250 |

76.9 |

|

|

History of PIH |

Yes |

75 |

23.1 |

|

No |

250 |

76.9 |

|

|

History of APH |

Yes |

84 |

25.4 |

|

No |

241 |

74.2 |

|

|

Any injury during current pregnancy |

Yes |

50 |

15.4 |

|

No |

275 |

84.6 |

Magnitude of preterm birth

The prevalence of preterm birth in this study was 12.8% [95% CI (21.0%, 29.8. %)].

Health care service-related characteristics

Out of 325 mothers, 240 (73.8%) had ANC follow up for their recent pregnancy, whereas about 85(26.2%) of them had no ANC follow up. Among those mothers who had ANC follow, 22 (6.8%) had at least one visit, 180 (55.4%) had 2 visits, and 38 women (11.7%) had 3 and above ANC Visits.

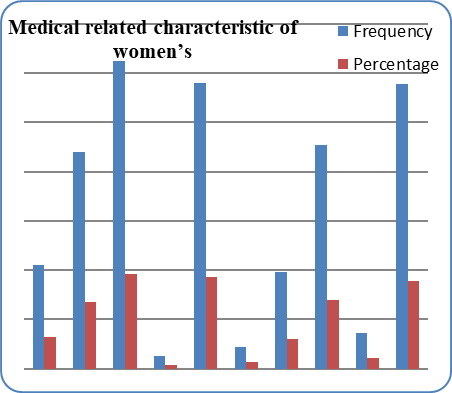

Medical-related characteristic of women

Among 325 women tested for Anemia, one third (98; 30.2%) were anemic whose Hgb concentration was below 11 g/dl. The majority of participants (312; 96.4%) were tested for HIV, among those tested 22 (7%) had positive results, while the rest had negative results.

Fig 3: Medical-related characteristics of women who gave birth in public hospitals in Harar town, Eastern Ethiopia, April 11 to May 17, 2019.

Factors associated with preterm birth

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, women who do not attending ANC follow up, maternal, hemoglobin level, history of chronic disease and History of APH were statistically significant. Women who didn’t attend ANC were 1.5 times (AOR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.7, 2.3), those who had a history of antepartum hemorrhage were 1.3 times (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 0.2, 2.7), and women whose hemoglobin were less than eleven were 1.4 times (AOR=1.4, 95% CI: 0.2, 2.2) more likely to give preterm birth than counterparts (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with preterm births among mothers who gave birth in Harar town public hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia, April 11 to May 17, 2019.

|

Variable |

Preterm birth |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

|

|

Yes |

No |

|||

|

Residence Urban Rural |

34(23.3%) 47(26.3%) |

112(76.7%) 132(73.7%) |

1 1.17(0.7,1.94)* |

1 1.2(0.3,1.6) |

|

History of preterm Yes No |

36(42.4%) 45(18.8%) |

49(57.6%) 195(81.2%) |

3.1(1.8,5.3)* 1 |

2.6(1.3,5.2) 1 |

|

Pregnancy type Planned Unplanned |

42(23.3%) 39(16.9%) |

138(76.7%) 106(73.1%) |

1 1.2(0.7,2.0)* |

1 1.6(0.4,2.5) |

|

Do you attend ANC Yes No |

60(25%) 21(24.7%) |

180(75%) 64(75.3%) |

1 1.3(0.5,1.8)* |

1 1.5(0.7,2.3)* |

|

Inter birth interval <24 Months ≥ 24 Months |

55(24.3%) 26(26.3%) |

171(75.7%) 121(73.7%) |

1.2(0.6,1.90)* 1 |

1.3(0.4,2.0)* 1 |

|

History of Abortion Yes No |

29(29.3%) 52(23%) |

70(70.7%) 174(77%) |

0.72(0.42,1.22)* 1 |

0.5(0.2,1.2) 1 |

|

History of APH Yes No |

56(66.7%) 25(10.4%) |

28(33.3%) 216(89.6%) |

1.5(0.8,2.3)* 1 |

1.3(0.4,2.7)* 1 |

|

History of PIH Yes No |

20(26.7%) 61(24.4%) |

55(73.3%) 189(75.6%) |

0.8(0.5,1.6)* 1 |

0.7(0.3,1.2) 1 |

|

Onset of labor Spontaneous Induced |

69(24.5%) 12(27.9%) |

213(75.5%) 31(72.1%) |

1 1.2(0.5,2.45)* |

1 1.3(0.3,2.8) |

|

Hemoglobin level <11g/dl ≥11 g/dl |

26(26.5%) 55(24.2%) |

72(73.5%) 172(75.8%) |

1.1(0.6,1.94)* 1 |

1.4(0.3,2.2)** 1 |

|

Hx of chronic disease Yes No |

27(25.7%) 54(24.5%) |

78(74.3%) 166(75.5%) |

1.9(0.6,2.4)* 1 |

1.3(0.4,2.3)** 1 |

|

Hx of malaria attack Yes No |

9(25%) 72(24.9%) |

27(27%) 217(75.1%) |

0.9(0.4,2.2)* 1 |

1.2(0.7,2.2) 1 |

P-value ≤0.05 is said to be statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of preterm births in this study was found to be 24.9% (95%CI 21.0, 29.8). These findings were consistent with the study conducted in Brazil (21.7%) [15], Nigeria (24%) [16], and Jimma (25.9%) [15]. The findings in this study were higher than the cross-sectional study conducted in India (15%) [17], Kenya (18.6%) [18], Gondar town (4.4%) [19], Debremarkos (11.6%) [14], Bahir dar (11.7%) [20], and Tigray (13.3%) [21]. This discrepancy might be due to differences in sample size, study area, study population, and intervention done toward pregnant mothers as well as socio-demographic characteristics.

Mothers who had a history of antepartum during current pregnancy were 1.3 times more likely to have preterm birth compared to counterparts. This was consistent with the study conducted in Tehran [22], Kenya [18] and Debremarkos [14]. These might be the due consequences of anemia following bleeding predispose to hypoxia and preterm to the new womb.

In this study, mothers who had no ANC follow up were 1.5 times more likely to deliver preterm birth than counterparts. This is in line with the study conducted in Cameroon [23] and Debremarkos [24]. The association might be due to antenatal visits of the pregnant mothers that are very important as they provide chances for monitoring the fetal wellbeing and allow timely intervention for feto-maternal protection. This may be described to the routine provisions of nutritional and medical advice or care and supplementations offered during ANC visits.

Mothers who had interbirth intervals at less than 24 months were 1.3 times more likely to have preterm births compared to mothers who had interpregnancy intervals greater than or equals to 24 months. These are similar to studies in Kenya [18] and Debre Markos [14]. These might be due to the existence of unidentified risk factors that precipitate preterm births in mothers with short interpregnancy intervals as well as maternal-related problems such as inability to take care of close birth intervals which might be due to socio-economic status.

Women who had a history of chronic diseases were 1.3 times more likely to deliver preterm birth than counterparts. These were in line with studies conducted in Malawi [25] and Debremarkos [14]. Maternal chronic illnesses may alter or limit the placental delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the developing fetus, possibly resulting in fetal growth restriction. In addition, they can increase the risk of preeclampsia and, thus, increase the risk of preterm birth. Therefore, acute maternal medical conditions might lead to preterm birth.

Finally, women whose hemoglobin level was less than 11g/dl were 1.4 times more likely to deliver preterm birth than counterparts. These were in line with studies conducted in Malawi [25] and Debremarkos [14]. These might be due to the effect of anemia on the oxygen bearing capacity and its transportation tendency to the placental site for the fetus.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of preterm birth in Harar town public health hospitals is slightly higher than studies done in different parts of Ethiopia and still a major public health problem in the area. Not attending ANC, short interpregnancy interval (<24 months), previous history of APH, presence of chronic medical illness and low hemoglobin level (<11g/dl) were found to be statistically significant with the occurrence of preterm birth in the current pregnancy.

Recommendation

For obstetric care providers

For health institutions;

Strength and limitations of the study

Strength

Limitation

Since the study design was cross-sectional, it doesn’t show the temporal relationship between the cause and effect and didn’t incorporate the consequence and outcome of preterm babies.

REFERENCES